INTRODUCTION

The primary objective of this literature is to propose innovative solutions and interventions to address the challenges faced by the residents of Rolford City, located in the northwest of the United Kingdom. This thriving community has a demographic report that indicates over 51% of its population comprises children who live in poverty, which makes them more susceptible to digital exclusion and also deprives them of other benefits that modern technology can offer.

At the end of this assessment, after the living conditions of the individuals that were adversely affected by this complex problem have been carefully analysed then an innovative solution will be proposed to address the digital divide in the Rolford community. The proposed solution will be innovative and dynamic, aimed at improving the living conditions and economic prosperity of both the businesses and the residents of the entire community.

THE REVIEW OF DIGITAL DIVIDE LITERATURE

DEFINING DIGITAL DIVIDE

In today’s digital age, possessing digital skills is not just beneficial but increasingly essential for complete participation in society and the economy. Individuals lacking access to or proficiency with digital technologies encounter significant obstacles in accessing information, education, employment opportunities, and essential services. This digital divide perpetuates existing inequalities while creating new ones, further increasing the gap between those who can leverage technology for their benefit and those who are left behind. Therefore, bridging this divide is crucial for promoting inclusivity, equal opportunity, and economic empowerment in the digital era. (Shing H. Doong, Shu-Chun Ho, 2012)

The digital divide refers to the gap between different groups or regions in terms of access to and utilization of modern information and communication technologies (ICT). (Katie Terrell Hanna, 2001) These technologies encompass various forms such as telephones, television, personal computers, and internet connectivity. The divide can manifest in various ways, including disparities in infrastructure, affordability, digital literacy, and socio-economic factors, among others. Closing the digital divide is a crucial goal for promoting equitable access to opportunities and resources in the digital age. (Shing H. Doong, Shu-Chun Ho, 2012)

ANALYSING DIGITAL DIVIDE

The term "digital divide" has indeed led to more confusion than clarity, as noted by scholars such as Gunkel and Van Dijk. (Jan A.G.M. van Dijk, 2006) Their critiques highlight several key issues:

A THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK OF DIGITAL DIVIDE: THE MICRO-MESO-MACRO MODELS

According to theoretical models, the use of computers is considered the highest level of accessing information technology (De Haan 2004). The ability to use computers depends on possessing the necessary skills, which in turn depend on motivation. Without having passed any of the previous stages, people are unlikely to use computers for their personal needs.

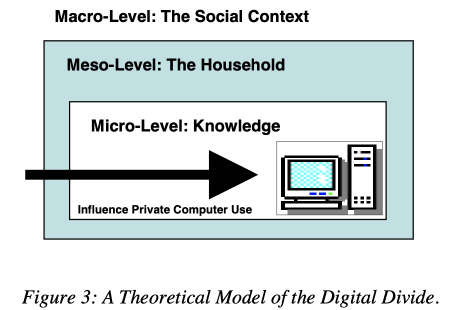

In order to fully understand the digital divide, it is important to analyse it through a multi-dimensional framework. This involves identifying early adopters and understanding their motivations for using computers for personal purposes. At the micro level, the impact of knowledge and human capital - such as education and computer literacy - is a key consideration. At the meso level, household settings play a role in shaping individual computer use. Finally, the macro level looks at group membership domains, including factors such as generation, gender, ethnic background, and national differences (see Figure 3).

Focusing on individual skills, knowledge or human capital includes both general and specific education and training, such as high school diplomas or vocational training (Becker 1964). Higher levels of education and vocational training are positively associated with computer usage, with computer literacy being an additional educational skill. People are more likely to use computers for personal purposes if they are introduced to them through work (usually in white-collar jobs).

The meso-level, which sits between the individual and societal levels, should focus on household composition and consumption restrictions, embedded within a socio-ecological framework (Watt & White, 1999). This framework includes habitation and technological environment. The incentives for children to use computers are clear: computer use allows them to play games interactively and facilitates their schoolwork (Leu, 1991).

When considering the computer usage of children, teenagers, and young adults, a common question emerges: how can their parents be encouraged to use computers as well? This issue is multifaceted, with concerns such as safeguarding children from accessing inappropriate internet content being paramount. The most effective approach is for parents to acquire an understanding of computer functionality and content control. Within families, computer usage patterns are currently reflected in the level of regulation and control (Beisenherz, 1988). The structure of consumption restrictions should reflect economic inequality (Ekdahl & Trojer 2002, Martin & Robinson 2004).

At a macro-level, several factors are identified as potential determinants of technology adoption: generation, gender, ethnicity, and regional differences. The theoretical approach that includes generations is based on a concept called "technical generations," which identifies four ideal types (Sackmann and Weymann 1995). The "pre-technical generation" (born before 1939) grew up in an environment without household technology. The "generation of the household revolution" (born between 1939 and 1948) was raised during the diffusion of basic kitchen technology like kettles and refrigerators into private households. The third "generation of advanced household technology" (born between 1949 and 1964) grew up with more sophisticated inventions like washing machines, stoves, and central heating. Finally, the "computer generation" (born after 1964) was raised in an increasingly digitalized home technology environment.

CURRENT ISSUES & TRENDS IMPACTING THE GLOBAL COMMUNITIES

Understanding the infrastructure behind broadband delivery is crucial for assessing digital access and connectivity. In the UK, most homes and businesses receive broadband through a combination of fibre-connected street side cabinets and copper telephone landlines. The proximity of a property to the street side cabinet significantly influences the broadband performance one can expect. (National Broadband UK, 2017)

If a property is located next to the street side cabinet, broadband performance can reach speeds of around 70 Mbps. Even if the property is farther away, approximately 1,000 meters, it should still experience relatively high speeds, typically around the 30 Mbps mark. This infrastructure setup allows for widespread broadband access across the UK, but the performance can vary depending on factors such as distance from the cabinet and the condition of the copper telephone lines.

Understanding the technical aspects of broadband delivery helps policymakers, service providers, and consumers alike make informed decisions about digital infrastructure investments, service offerings, and expectations regarding broadband performance.

Indeed, as the distance between a property and the serving cabinet increases, broadband performance can be significantly impacted by a phenomenon known as attenuation. Attenuation refers to the gradual weakening of signals as they travel along the length of copper wire, which is inherent in the physics of signal transmission.

When a property is over a kilometre away from the serving cabinet, attenuation becomes more pronounced, leading to slower internet speeds. The longer the copper wire, the greater the attenuation, resulting in weaker signals and reduced broadband performance.

For properties situated far from the cabinet, broadband speeds may become frustratingly slow, making it challenging for residents and businesses to access online services, stream content, or engage in activities that require high-speed internet connectivity.

Addressing such challenges often involves infrastructure upgrades, such as deploying additional cabinets, installing fibre-optic cables closer to properties, or exploring alternative broadband technologies to improve connectivity and mitigate the effects of attenuation.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the rapid development of ICT has reduced the socio-economic gap between regions. Early intervention by the government, stakeholders, and communal efforts will largely help restore the lives of adversely affected locals. ICT development, while not eliminating the digital divide, has had a significant impact on the global economy. This literature analysed the current issues and trends of the global impact of the digital divide. These analyses and theoretical models could give insights into solving this complex problem. After much consideration, this review has presented concise, precise, and logical insights into the issue. (Wambugu Naftaly Muriuku, 2016)